- Home

- Ben Neihart

Hey, Joe Page 4

Hey, Joe Read online

Page 4

He had gotten so close to fixing the jury. The first two marks had come so easily. In deliberations, they had turned to Seth with misplaced affection and admiration and taken at full value his claims that Mrs. Shaw's alibi for Schipke was reasonable, that the children had been coached to lies by social workers. As if he were the foundation's publicist, Seth had presented an argument that the foundation was above reproach because of the beautiful work it had done in restoring the orphanage building to its original splendor. Seth's marks had also gotten all tangled up in the judge's instructions about a "preponderance" of the evidence—curlicues, Seth thought, scrim work.

This morning, in secret ballots, the tally had stood at eight to four, with Seth, his two marks, and a fourth, whose identity he suspected—Rita?—but was still unsure of, blocking a conviction. The judge, in a calm written note responding to their standstill, had ordered the jurors to make one last try for a verdict before he declared a hung jury.

In less than an hour, Seth would get in the van and head back to the court building. He would change his vote. Perhaps, he thought, he could begin to change his ways.

The telephone rang. He threw his arm onto the bedside table and snatched the clunky receiver from its cradle. "Hello?"

"Hello." A wisp of a voice.

"Who is this?"

"Count your fingers and toes."

The skin across his shoulders and down his spine tingled. "Who is this?"

"Count your teeth."

"Who the fuck—"

"Seth!" A high, girly squeal, then sucking laughter.

"Tell me who this is."

"Death did to me short warning give ..."

"Who?"

"They'll find you hanging from the ceihng." The caller hung up.

Seth held the dead receiver against his chest for a moment before he got out of bed and plodded across the carpet to the far window. He pulled the curtain aside a few inches. Rain was skidding sideways, spattering against the glass. Down below, the media stood in lighted clumps, setting up for the dull footage they liked to shoot of the backs of the jurors being escorted to the vans. The judge, Seth guessed, had already announced that one way or another the trial would end tonight.

Away from the motel, toward the Quarter, work-duty prison inmates in orange coveralls erected crowd barricades for this evening's parade, the first of the new Labor Day weekend festival that the city was promoting as an upstart, late-summer Mardi Gras—funky, the mayor's office said, but without the racist history. Seth had done some freelance phoners and mail drops for the festival publicists, some packaged TV news puff spots, all of it good work, a testament to his camaraderie with the city's ascendant political powers.

The inmates tossed the barricades off truck beds, then chained them together along the curb. Bend over, lift, toss; catch, place, chain. Easy work for a prisoner, Seth thought; the fencing was lightweight metal, carnival grade. Just as the sight of the underworked prisoners started to inflame his temper, his eye was drawn to a lighted set: four cameras and a couple of reporters across the street from the motel in front of the narrow cement rectangle that announced the courthouse parking facility.

Being interviewed were five of the older orphans from Lady Rampart. Seth recognized them by their bald heads and matching construction boots. He had to give it to them; they'd scored a dramatic backdrop: tufted, stumpy palm trees waggling in the wind beneath a clearing sky of blue-black clouds shot through with orange and red. Seth watched until the boys had finished their say. As they piled into their Jeep and drove away, he let the curtain close.

6:00 p.m.

Sometimes, Wyatt K. was Joe's best friend. He was good for all the guy activities that you could fit into a day. Like mountain biking on the trail that ran beside the Mississippi River, or driving up and down Airline Highway in the early evening, chilling to an onslaught of metallic, whining Beastie Boy rhymes, or smoking a fatty in Joe's bedroom before school. But there were other times— plenty of them—when Joe couldn't help but think of Wyatt K. as an opponent, a quarry, someone to fuck with and beguile.

Wyatt had just called to say that all of a sudden his parents were taking him to Houston for the Labor Day weekend. He was trying to be sincere, but he didn't have any of the right words.

Joe was letting him bumble. He listened in silence as Wyatt listed the places he was going to visit.

Astroworld.

One modem art museum. Didn't remember the name. Wyatt thought it was Joe's kind of thing more than his own. It was, but still Joe didn't say anything.

Three malls.

The sloppiest Tex-Mex restaurants, where he was going to smother his tacos in the greenest, pulpiest poblano.

Rice University, where Wyatt's dad had gone and where he wanted Wy to go, too, and play soccer, and turn himself into an electrical engineer.

"Joe—you there?" Wy asked. He sounded as if he'd just taken a bite of banana.

Joe didn't answer.

"I'm sorry, boy. I didn't want to bag on our plans."

"Whatever."

"Okay, I won't go. What do you want from me, boy?"

"It's okay, Wy. I'm sorry for acting like a wussy."

"Someone else can give you a ride to the Quarter. Call Shelby."

"I probably won't go. It's not like I was that into it."

"What are you gonna do, then?''

Joe was looking out his bedroom window. "Hang with my mom. Talk on the phone. Rent a movie. Give fashion." There was nothing going on in the neighborhood. Lawn sprinklers swirled. Chubby husbands and wives took power walks, slicing their arms through the air. The sun was orange with a few dots of red, like a fertilized egg yolk.

"Don't smoke it all up," Wy said. "Save some for me."

"You know I will," Joe said, and rolled onto his stomach. "I always do."

"Yeah..."

"That's the thing. I'm always good, boy. To you. I'm always a good friend to you."

"This is totally sick. You're making me feel bad."

"I'm not trying to."

After a brief pause, Wyatt said, "Maybe you are."

"You talk like that all the time. Just to make me feel like shit."

"Shut up."

"Whatever," Joe said. "Are you taking your skateboard?"

"My dad says I can't."

"I thought your dad was cool."

"He's pretty cool, but he wants this to be like my kind of mature side. To be convinced that I can handle it at Rice. Be in Houston or whatever. Because he thinks this city's for shit now and isn't gonna get any better."

"That's bullshit. I don't ever wanna live in some other city."

"I don't know. I don't think about it. Well, sometimes I do. Maybe there aren't gonna be any opportunities when we get out of college. That's what my dad says."

"Your dad who won't let you pack a totally packable skateboard in your suitcase."

"Yeah. Him."

"Sucks. Some sweet ramps at the malls."

"You took your board to Houston?"

"Don't say it like that. You know I suck. You're stronger at that. It's your thing, Wyatt." Joe listened with disgust to the softhearted admiration that had crept into his voice. And it wasn't just admiration, not merely, not simply. It was something more, and that was the problem of his life.

There was silence, and then Wyatt said, "I'm pretty good, aren't I?"

And Joe couldn't help himself. He had to say, "You're actually the best."

After he hung up, he scrambled out of bed and into the hall. "Mom," he called. "Mom!" His voice bounced off the mirrors and family photographs on the walls before it soaked into the floor. "Wyatt K.'s going to Houston. Can you zoom me downtown?"

No answer.

He thudded toward the living room and then into the kitchen; ripped open the refrigerator door and peered inside.

His heart had been set on a fried oyster po-boy at the St. Anne Deli. His tongue plumped up with taste memory: crackly, oil-dripping batter; smooth mayo spiked with hot sauc

e; shredded white lettuce; meaty slices of warm tomato. And then a $1 twenty-ounce draft beer from the bar across the street. Good Friends! It was a rush to walk in there from right off the street when you were hot, you were dragging ass, your skin was filmed over with sweat, your throat was dusty, closing up. You pushed open the saloon doors and—boom! A.C. blasting into the dark, guys shooting pool, ceiling fans swirling, disco tunes boring into your bones. Fuck, boy, some muscle man chances a smile your way. Grab your beer and run or it might turn into more of a night than you expected.

"Mom!" Joe called again, slamming the fridge door shut. "Hey, Mom!"

Still no answer. He listened for a moment, but there were no television or stereo noises. He went to the window above the kitchen sink, looked out into the backyard. The plants were looking rough: burnt edged, droopy from too much rain. The grass, too, looked weak, almost transparently yellow.

And there was Mom, stretched out on one of the stone benches in the center of her little rock garden. A bare foot dangled on the crust of a barren, neatly swept Zen sand plot; an arm covered her eyes; hair hung away from her face, revealing her vulnerable temples; a book rested on her belly. Joe recognized the fake-marble cover; it was one of those lawyer books.

No wonder she fell asleep, he said to himself, turning away from the window.

He spun some notepaper off the roll that hung beside the telephone and wrote a note promising to be home by ten-thirty, his curfew.

He changed into a T-shirt and cutoff army pants, rubbed some more deodorant beneath his arms, gargled with Listerine, and then busted out the door. ' 'Hold me, ba-by, drive me, cra-zy," he sang along with the sugary track in his head, crossing the front lawn. He took pains to make deep footprints in the bristly yellow grass. As he reached the curb, a voice called out behind him:

"Joe, what's up?" It was Al Theim.

Looking over his shoulder, Joe said, "What's up with you?"

"I asked you first."

"Yeah?"

"I did."

"Yeah?" They hadn't really talked all summer, not since one night in June when they were fucking around as they always had, wrestling and whatever in Al's bedroom, and Al, laughing, had Joe pinned beneath him, knees holding Joe's arms to the floor, and as if a lifetime's worth of contempt had built up in him, called Joe "the fag of the year." The words had hung there in the chill air of Al's room as if writ large on a banner that fluttered above a stage that Joe was crossing to accept his award.

Now Al walked slowly down the mild slope of his lawn toward Joe's driveway. His breath came with some effort, as if he'd just run wind sprints. He was pulling on a denim baseball shirt that matched his baggy shorts, and a pair of dog tags hung on a length of rawhide around his neck, bouncing against his chest in time with his strides. He was barefoot.

"I wanted to ask you something? I don't ever see you around. What are you doing with yourself? Like, what are you doing this weekend?"

"Well, you can see I'm like taking a walk."

"Yeah."

"Yeah."

"I'm so bored, man. I've just been doing shit with my sister.''

"Oh," Joe said.

"Where you going on your walk? Can I come?" Al stood on one leg, shaking a cramp out of the other. All summer long, he'd been Mr. Buff Cardiovascular Workout. He drilled himself through push-ups and crunches and he walked on his hands. He was building himself into someone new, growing up, leaving behind the fag of the year. At his current frantic pace, he'd soon be hanging with the necky Rods who'd always steered clear of Joe.

"I'm catching the bus," Joe said. "Going to the Quarter."

"Come here," Al said, leaning against the bumper of Mom's car and scratching his back. "I said I'm bored. I want to talk to you man. Let's clear shit up."

Joe looked at his sneakers, shaking his head. "Man, talk to someone else. It makes me feel really stupid. I don't want to talk to you."

"Why can't we just hang? We can like hang. I don't hold any of that against you. I never told anyone anything. Forget that. We can, like, hang. Come on."

Joe felt every inch that was between him and Al, and was glad for it. "It doesn't make any sense for us to be friends. I'm not screwing with you, so you should respect me."

Al's eyes were fixed beyond Joe, as if an axman approached. Joe didn't dare look over his shoulder. "Whatever," Al finally said, pulling back his shoulders so his dog tags swung. He stepped away from the car, heading home. "Let me know when you grow one."

Joe watched him swagger away. ''I've got a lot to learn, dude, and I admit it," he called, "but I'm not the only one."

Al held up his hand and gave a mincing little backwards wave.

"You suck," Joe whispered.

* * *

He hiked through his subdivision to Metairie Road, waited twenty minutes for the bus to the Quarter, boarded, had almost fallen asleep when he opened his eyes to see the puny, enticing downtown skyline against the pink clouds. He hopped off the bus at glass-sparkly, boom-boxy, every-kind-of-peoplesy Canal Street. The Mississippi River and the radiant hotels and the fussy gift shops were at one end of Canal. Joe shielded his eyes from the bolts of sunlight that bounced off the surfaces; then he turned and walked in the opposite direction.

Wyatt Who? he asked himself.

Al Who?

He caught the streetcar uptown, jumped off at Broadway. Before he knew it, he'd broken into a jog. Six blocks, seven blocks, eight blocks, ten—and why not? The sidewalks were wet, and there were street musicians providing a lazy soundtrack, and the sun-cooked, rain-glistening vines and flowers and leaves emitted a sly fragrance that melted your brain and heart so that all you wanted to do was cry out to someone—anyone who'd tangle up with you—I love you. Hey, I love you! He skidded to a stop in front of So-So's, the music shop that was his and Wyatt's favorite hangout—even though it was also sometimes the favorite of other new-bie tenth graders from rival high schools. He busted in the front door and shouted hey to Kel, the studly woman who ran the place.

"Hey, Joe," she said, and then continued with her phone conversation.

"My girl," he said, holding up two fingers in a peace V. He pulled the door shut behind him and walked past her down the narrow aisle of metal shelves and displays of compact discs and cassettes and vinyl.

"I tried to read it," she was saying to whomever. "I don't understand what she's getting at. It's the same point in every chapter. I think it's the same argument, which I like get, but it's not going to change my mind more than once. Do you know what I'm saying?"

Joe got comfortable in front of a circular turnstile display of World Music cassettes. Some of it he liked. There was a thing called pop-rai, from Algeria, that had gotten his ass shaking at Jazz Fest this past May, and of course he always had a fond ear for salsa music, especially when the singer made you feel like he was lying right beside you on a huge towel on a hot beach.

He looked up from the display at Kel. Fuck if he wasn't totally unfortified against her charms. Kel. Crunchy Kel. She was around thirty or thirty-one, Joe had heard, and she was always looking fly, always hyped on the latest fanzines and demo tapes. She was loose with enthusiasms; she liked to check out your rings, your tattoos, your chokers. She was taller than Joe and even skinnier than he was, had the pointiest elbows that he'd ever touched. She dressed in gutsy little skirts and T-shirts, tan bricklayer's boots. She liked to custom-make her clothes, tear off a sleeve and sew it to a different shirt. Her hands were knuckly, like Joe's mom's, and she had long black hair that always smelled like the ocean and was so shiny that you could almost see yourself in it. The girl could give runway.

Mouth agape, Joe drifted to the minidisplay of rap CDs that was propped against Kel's cash register stand. Her muscley white knee peeked from behind it. Today's skirt was tan, and her red T-shirt fit tight on her chest and upper belly, like a tube top.

"That shit hangs real cute on you," he blurted.

She scrunched up her face in thanks.

"Oh, God, I

'm sorry; you're on the phone. I should let you finish."

She nodded, and then she let her tongue poke out between her lips and crossed her eyes. She pointed at the phone with the middle finger of her free hand.

Joe smiled. She was having a lame conversation. She had confided in him, made him her ally.

He circled back to the World Music display, lingered for a moment, and then continued to the back of the store. It was dark and cooler back here in the lounge. The furniture was totally easygoing: two floppy red burlap sofas; a brown vinyl beanbag bed; several freestanding green metal ashtrays; and miniature brass temples dangling from chains in which patchouli and lemon-willie incense burned. The tiny, mighty stereo was back here, too, its instrumentation emitting comforting greens and blues. On low volume, Kurt Cobain sang, "choice is yours / don't be late" over hollow red guitar noises.

Joe threw himself onto the closest sofa. The coarse burlap scratched his neck and elbows. He knitted his fingers together behind his neck and closed his eyes.

One night, after the store closed, Kel had shared a joint with him and then had made him try on her olive velvet shirt and pair of red corduroy shorts—just to satisfy her curiosity. She stood right beside him, wearing just her panties and bra, in front of the mirror on the storage-closet door. She made him undo the velvet shirt's bottom two buttons to show off his belly button. "Fabulous hip bones," she murmured. Joe slouched closer to the mirror and gazed into his own eyes. He felt pale with happiness. The clothes looked as if they'd been designed just for him. It was the same pulled-together feeling he'd experienced every now and then when he was at the beach, his hands and feet salt bleached and sand scrubbed to immaculateness.

And then, a little bit drunk and exuding his usual ornate scent, Wyatt K. had snuck up behind Joe and touched his shoulder.

"Doesn't he look...," asked Kel's voice. "You know?" She was somewhere in the room. Anywhere. A corner.

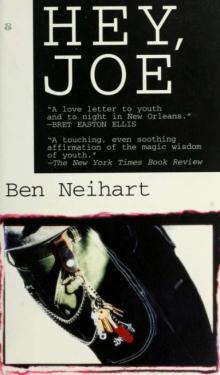

Hey, Joe

Hey, Joe